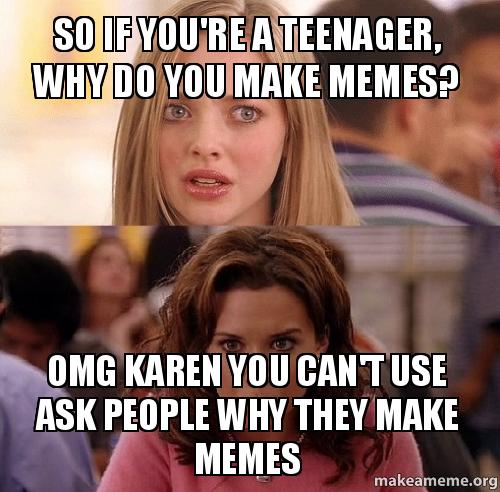

Tackling the subject of teens and memes is a bit…fraught.

Last week, the New York Times published my article, The Role of Memes in Teen Culture. The article is aimed at parents (and grandparents and teachers), and it’s intended purpose is to help adults understand why and how teens use memes. It grew out of my personal experience, as so many of my articles do. When I learned, in early January, that the United States killed Iranian Maj. Gen. Suleimani, my stomach dropped. I was engaged to a Marine during the first Gulf War; I know how quickly these things can escalate, and I know that “troops” are actually sons and brothers, sisters, classmates, spouses and children.

My teenagers came home that day laughing about the prospect the war. World War III memes were trending.

Sure, some of the meme were funny. But I’m a parent. Of boys. In the 21st century. One of my primary goals is to raise boys who are decent human beings. I think I’m doing a pretty good job, but like every “boy parent” I know, I’m deep-down terrified that I might be raising entitled clods.

So, I turned to my Facebook group. (I can hear my teens now: “Ok, Boomer!”) I asked other parents if their kids were sharing & laughing at WWIII memes. The answer, almost unilaterally: Yes. Like me, many of the parents were disturbed and distressed:

I’ve seen the memes and it hurts my heart to think that anyone would laugh in a time of such uncertainty and distress….

…I hope we, as parents, can take this moment to lead by example and show our children that this is not a game. This is real, this is serious and this situation demands cool heads and forward thinking perspective….

I’m a writer, so when I’m faced with a subject of interest that I don’t understand, I research and write. I dug in; I looked at a lot of WWIII memes and read other articles about how and why people use memes. I wrote about what I’d learned; my Jan. 6 subscription newsletter included these sentences:

I don’t think war or wildfires are a laughing matter. But I don’t think we’ll help anything by browbeating our boys for looking at, laughing at or sharing memes.

Then, I pitched the New York Times. Parents, I knew, were looking for guidance and I wanted to share what I’d learned. Most of all, I wanted parents to relax. I wanted them to know that kids who look at, laugh at and share memes — even dark and disturbing ones — are not terrible, insensitive people.

I learned a lot while reporting and writing the article. I learned even more after it was published. There’s currently a fantastically thought-provoking conversation unspooling in the comments section. Here’s what I learned writing about teens and memes:

1. “Teens” is a wide age group. There’s a big difference between a 13 year old and a 19 year old, as my very own 19-year-old reminded me after the article was published. And I confess: when I was working on the article, I was thinking of 13 and 14 year olds, not 19 year olds. There’s a huge difference in how young teens and older teens evaluate and interact online content.

2. Teenagers are the experts in teen culture. I knew this one heading in. I knew that teens would be the only ones who could accurately explain how and why they use memes because they are the only ones who can accurately describe their thoughts, responses and motivations. I also knew that it would be potentially difficult to get teens to share their thoughts; teens often don’t trust adults (often, for good reason!).But I was on a tight deadline; I needed to get this article in sooner rather than later, which meant I didn’t have time to cultivate relationships with teenage sources. And, quoting teens in the New York Times is a bit dicey. Certainly, writers have to get parental consent before interviewing and quoting underage sources, but even then, it’s important to consider how the adult version of that child might someday feel to find the words he said at age 14 immortalized in the newspaper of record.

That said, multiple young people have called out what they consider my questionable (at best) understanding of teens and meme culture. Halley said,

As a teen, I must quote Luke Skywalker, “Amazing, everything you just said was wrong.”

AA said,

As a teenager, I find it absolutely hysterical when the NYT publishes articles that try to analyze teen culture. These are articles are so far off the mark. Memes do not embody the teenage psyche, nor are they emblematic of deeper problems. Anyhow, for parents reading these articles to better understand their children, please understand that all teens find this hilarious.

And then, when adult asked AA to please explain more, AA said,

I think a lot of adults underestimate just how much teens feel things, in part because technology has kept to closer to the world that you spoke of being removed from as a teen. Honestly, the most important way to communicate way with your teen is to take them seriously and not belittle the world they live in, or dismiss memes as unhealthy coping strategies.

Teens are the true experts on the teenage experience, and we must listen to them.

4. The generation gap is alive and well. One 19 year old fan said,

The article is well-written, but you can really tell is was written by a Gen X who has absolutely zero connection to meme culture other than the snippets she hears her kids talking about.

All in all, younger comments said the article misrepresented the relationship today’s teens have with memes, and older readers said stuff like this:

Parents shouldn’t surrender to the dominance of memes and social media in the lives of their children. They should fight against it. Parents should encourage their kids to read reliable sources of news such as this newspaper. Memes are silly, childish fads.

and

When I was 13 and 14 we trapped mountain beavers (a groundhog-sort of animal, not the true beaver) in the local gulches with leghold traps we bought at the local hardware store. …Our moms put up with us boiling the heads down on the stove to clean the skulls for mounting….Now that was ‘teen culture’!

5. Teens want, need and deserve private spaces. Teens don’t want adults intruding on teen culture. Never did, probably never will. And you know what? I think that’s OK. The adolescent years are all about separation and individuation; it’s when teens discover themselves and become independent. Teenagers need our guidance, but they deserve some space as well, and based up these comments, I think teachers and parents better stay away from memes as teaching tools. As Nate so eloquently put it:

Memes are an outlet for young people. Turning them into a teaching opportunity, using them in classrooms, etc. will push teens to other mechanisms. This is the equivalent of your high school history teacher using a rap/hip hop song to teach you about the Declaration of Independence.

Stop looking for ways to manipulate your children and teens into acting and thinking like adults. Talk to them like they are people. Listen. Answer questions. Stop the pretending and manipulating and using their culture under the facade of “teaching”. All you are really accomplishing is to get in the way of their self expression and the outlets they use to communicate with their peers.

6. The kids are all right. Remember how this article was borne of my fear that my boys might actually be insensitive clods? They’re not.

My boys knew I was excited about this article, my first for the Times. Because they knew how important it was to me, they held their tongues; they did not say, “YOU? Why are you writing about memes?” They didn’t even roll their eyes at me.

And when it looked like the article wasn’t going to be published — because it was the end of January and WWIII memes were old news — my 14-year-old consoled me with a hug. When it published, he fist-bumped me and offered his congrats.