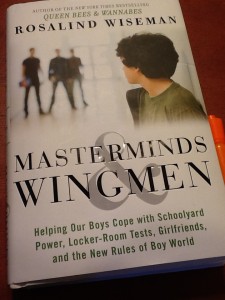

We recently talked with Rosalind Wiseman, author of Masterminds and Wingmen: Helping Our Boys Cope with Schoolyard Power, Locker-Room Tests, Girlfriends, and the New Rules of Boy World, via Skype. We hoped to post the audio and video for you, but we had some technical difficulties on our end. So we’re posting the transcript instead. Enjoy the conversation!

Jennifer Fink: Your book is going on my must read books list for parents of boys, and I don’t say that lightly at all. One of the things I really enjoy is that it doesn’t just talk about what the issues are. You give some very, very specific suggestions for how you can talk through some of these issues with boys in positive ways.

Rosalind Wiseman: I don’t think there’s a point in talking about problems if you can’t think through how to do something about it. I know it’s harder to talk about the solutions than it is to talk about the problem, but the benefit I had was that I had boys (the 200 boy editors who helped Wiseman with the book) telling me things like, ‘Okay that advice you just told parents is terrible.’ I had the benefit of having these guys telling me when I was wrong.

JF: Was it easier, in some ways, to talk to those boys than it is to talk to your sons?

RW: Are you kidding? For sure. Frankly, not only is it easier to talk to other people’s sons, it’s often more enjoyable. They tell you the truth. They laughed at my jokes and they don’t make me feel stupid when I get something wrong. They don’t roll their eyes at me. It’s so much easier!

JF: One thing you write about in the book: it’s not uncommon, for boys of all ages, to respond to ‘how was your day?’ with ‘fine.’ And you don’t get anything more than that.In the book, you write that sometimes it’s better just leave them be, to let them have some time. I’ve noticed that my boys will wander into the kitchen or wherever and start talking when they want to talk, but waiting isn’t always easy for parents to do.

RW: Yes, but aren’t we supposed to be the ones who have impulse control? Aren’t we the adults here? Aren’t we supposed to realize what is effective and ineffective, and then realize when we’re being ineffective to actually try to address that?

If we claim to be the adults that we are, then I think we need to act like it, and that means trying to manage yourself and being self-reflective about the things you’re doing that can contribute to the communication breakdown. It’s really incumbent upon us to be self-reflective on what we’re doing that contributes to the problem.

JF: In the book, you make it clear that you don’t always have to have a deep heart-toheart conversation to get a message across. You don’t have to have the boy say, ‘You know, mom, dad, you’re right. I understand this is a big issue.’ It’s more of a low-key approach. Can you elaborate on that for people that may not have read the book yet?

RW: You cannot expect a Hallmark moment with your child. That is completely unrealistic. If you ever get one, that’s awesome. Bank it! But usually when there is a difficult problem or conflict, it’s probably causing your son some amount of discomfort, anxiety and embarrassment to have the conversation with you, so to expect him to listen to it, process what you’re saying, be able to speak about it and then in some way acknowledge it and thank you for it in the same conversation, is, I think, a bit unrealistic.

I think that our sons must treat us with dignity and I’m really adamant about that with. [When I was working on this book] I was really struck by how often the boys felt they could get away with not respecting their mothers and not treating their mothers with dignity.

I really believe that you can say your piece. You just need to be clear about what it is and then allow your son to think about what you said, and then loop back with him the next morning or whenever. So if you have a difficult conversation night before, on the way to school in the morning, it’s appropriate to say, ‘Have you thought about the conversation we had last night? I’d really like to know what you think.’

JF: You mention the SEAL process throughout the book. Please explain what that is.

RW: SEAL is the strategy that I use to help people think through a social conflict with someone, so they can speak their truth to someone they’re worried about or angry with. SEAL: S stands for the Stop and think about where you confront the person. E is Explain exactly what you don’t like and exactly what you want, even it seems incredibly obviously to you. A is Affirm, Acknowledge. It’s affirming your right and the other person’s right to be treated with dignity, and for acknowledging anything that you did that contributed to the problem. L is Locking in the relationship, Locking it out or taking a vacation. When kids are in conflicts with their peers, one of the things I want them to think about is that they can decide not to be friends with people or they can decide to take a vacation from someone. As a parent you don’t get to lock out your kid. You don’t get to say like, ‘Wow you’re super obnoxious and I just can’t do it anymore.’ I mean I guess you could…

JF: You could take a mini-break but you’re not going to give up on your kid.

RW: Right.

The S and E and A are really helpful because they stop you from reacting in the established patterns that you have of reacting when you’re angry or frustrated. I want parents, when they’re thinking about communicating with their children about difficult things, to really think about the environment in which they are broaching the subject.Don’t have these conversations in front of other siblings because the only thing that’s going to happen is the other siblings are going to smell blood and attack or tease that kid and then the kid is going to get defensive and run away or be really mad at you.

JF: Before, you mentioned dignity and the importance of insisting that we be treated with dignity by others and by our children, but that can be complicated. Sometimes our kids have people in their lives who are not great role models, as far as treating other people with dignity. What advice do you have for parents and educators who may be trying to help kids who have some negative role models in their lives?

RW: This gets really tricky because you might be talking about a spouse, an ex-spouse or an ex-partner. If it’s that kind of a person, the way in which your child sees you handling it is really important because your child is going to see people abuse power and treat people in degrading ways. That’s a fact. So let’s say you have an ex-partner who’s not treating you with respect or treating your kid with respect. Say something like, ‘You have the right to tell me when you’re upset or when you’re angry about something. You do not have the right to talk to me,’ — this is where the E comes in — ‘in a way that’s condescending or puts me down.’ And if the other person says, ‘Well you’re just being too sensitive, ’ it’s really important to say, ‘But it’s my right to have the feelings that I have and you cannot take that away from me. You and I can have a disagreement about the facts but you cannot take away my right to demand to be treated with dignity, to feel that my voice can be heard. And that’s the same with my child. You can disagree with his behavior. You can disagree with the facts of the matter, but you must treat my child with dignity.’ When you do that, you’re literally countering much of the negative role modeling.

But the other thing I want to put out there is that a lot of parents have boys who are cussing at them and calling their mothers a bitch. It’s a real place of shame for a lot of parents and I feel horrible for them when they tell me, ‘My kid calls me a bitch. My kid says F* you.’ That’s a place where the parent has lost being an ethical authority leader to their sons, and that’s not just a small thing. It’s a big thing. It’s something that the parent needs to address effectively because boys need ethical leaders, ethical authority figures in their life.

JF: The easy thing for parents to do at that point is to say there’s nothing I can do about it. But there are ways parents can step in and say, ‘You know what, I’m not taking this anymore,’ in a respectful way, right?

RW: What you can say to your son is, ‘You know I’ve been really thinking about this. I’ve been doing some really deep reflection and there are some things I’m not doing right by you, and one of those things is that I’m allowing you to say these words to me and speak to me in this way. And I am going to do my own work to be the parent that you deserve, which is a parent who demands respect and demands to be treated with dignity.’

Now your child is probably going to say something super obnoxious back, and I would say, in response, something like, ‘I am not going to accept that language anymore. I’m not going to continue having a conversation with you when you speak to me like that. I want to have a conversation with you, but not on those terms. I am going to work on this. I can only work on myself with this. I really want to be able to have a better relationship with you. I am working on it and I hope you meet me half way.’

JF: One final question: In the book, you write about the Act Like a Man Box, the narrow definition that a lot of our boys have and that our society feeds them about what it means to be a man, to be a boy. Do you think that today’s boys are actively working to expand the box?

RW: Some are. There are some kids who are really going to teach us about what acceptance means. I really believe that there is a very healthy percentage of young people who a more astute understanding of race and class and gender than we do as a generation, and they understand how these things interweave.

Of course, there is a group of boys and girls, who, for a variety of reasons, are extremely invested in adopting the most aggressive definition of gender as a way to get power. And that is often really reinforced by adults in their live who are invested in that system as well and believe that examining it is a rejection of their entire way of being.

We’re in really interesting time because we’ve got some kids who are really acting out in an incredibly regressive ways. We also have a lot of kids who have a very deep understanding of how these issues impact their lives. This is why I love working with young people: I learn a lot. I learn a tremendous amount.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.